The NTLM Authentication protocol is a challenge/response mechanism that proves to a server or a Domain Controller (DC) that the user knows the password associated with an account.NTLM authentication can be used for both domain and local accounts.

This authentication mechanism is session-based, meaning that the user is authenticated as long as the TCP session between the client and the server is maintained. In other words, for NTLM authentication to succeed, authentication messages must happen over the same TCP connection. If the TCP connection drops in the middle of the authentication process, then you would have to start the process all over again.

In contrast, for example, for request-based authentication; where you need to provide an authentication token on every request.

Now, what is the mechanism to maintain a TCP session open? Well, this is controlled by the HTTP response header “Connection”. If the value is “keep-alive”, the connection is persistent and can be re-used. If the value is “close”, then the TCP connection will be closed and the client will need to create another connection for the next resource it asks.

Can NTLM behave like a request-based mechanism?

Yes, under certain circumstances. Just keep in mind that a request-based mechanism increases network traffic as the client will need to supply authentication details on every request.

As NTLM is a challenge/response process, the client needs to send two requests in addition to the initial anonymous request. In it simplest form, NTLM is comprised of:

-

The client sends a first anonymous request.

-

The server returns HTTP 401 indicating user that it supports NTLM.

-

The client sends some information, and the server sends another HTTP 401.

-

The server allows access, HTTP 200.

So, two HTTP 401’s followed by an HTTP 200.

General process (a bit more in-depth):

-

The client sends an anonymous request to the server. The client cannot know in advance, that the server requires authentication.

-

The server lets the client know that the supported authentication mechanism. This is achieved by the server responding with a 401 with a response header “WWW-Authenticate: NTLM”.

-

The browser opens a pop-up for the user to input their credentials.

- The browser re-issues the request with the name of the user it wants to connect-as. This is appended in the request header.

Authenticate: T|RM ..."

- The server receives this request and generates a random string.

- The client browser will ask the Windows API to encrypt the random string with the user’s password hash and send this to the server.

- The server sends the same information to DC, as well as the client response so DC can make its own calculation with the password it has in its database for the user who is trying to authenticate.

- The DC compares the result from its own calculation against the result from the client that the server forwarded to DC. If this value matches then DC sends a session key to the server and the server will allow access to the resource, if not match, DC will send back an error to the server and the server will send a 401 to the client.

So, the idea is that the client and the DC will perform some calculations, if they match, we know that the user provided the correct password for that account.

What calculation? Although algorithms might have changed by now or I may be outdated, procedure is roughly the same:

-

MD4 algorithm is applied to the user password. This results in Value1.

-

The uppercase username is concatenated with the uppercase target realm, and the HMAC-MD5 algorithm is applied to this value using Value1 as a key. This results in Value2.

-

A random 8-byte client nonce is created.

-

The server challenge is concatenated with the client nonce, and the HMAC-MD5 is calculated using Value2 as a key. This results in a 16-byte value(Value3).

Both, the client and the DC perform this calculation to obtain Value3 and send this value to the server.

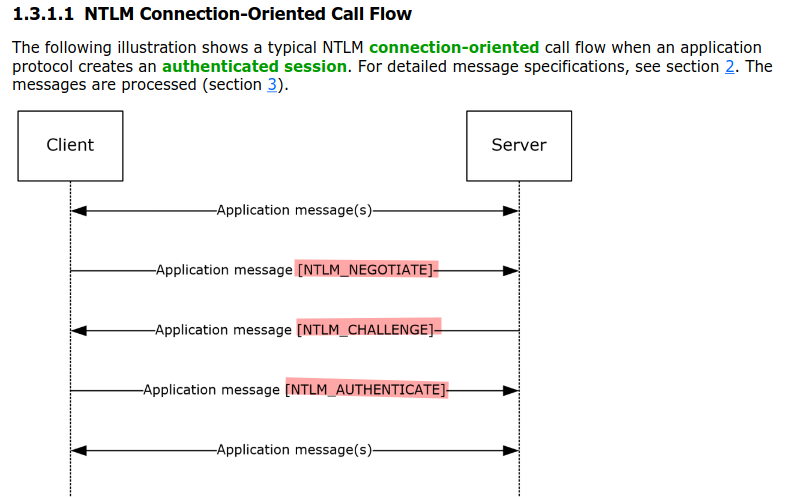

If we take a look at the definition of NTLM, we can see that it is comprised of three messages:

- NTLM_NEGOTIATE

- NTLM_CHALLENGE

- NTLM_AUTHENTICATE

Let’s explore each of these messages with an example:

Real-world example

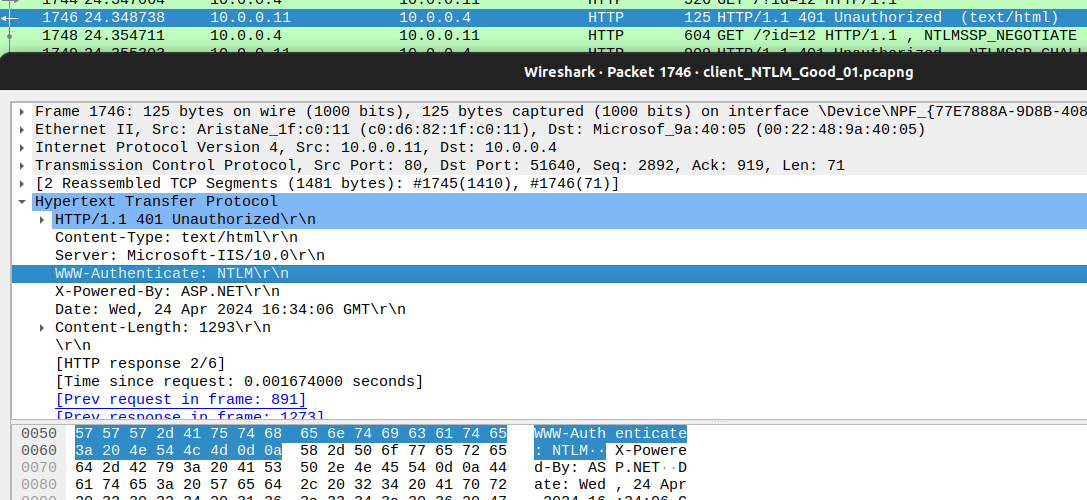

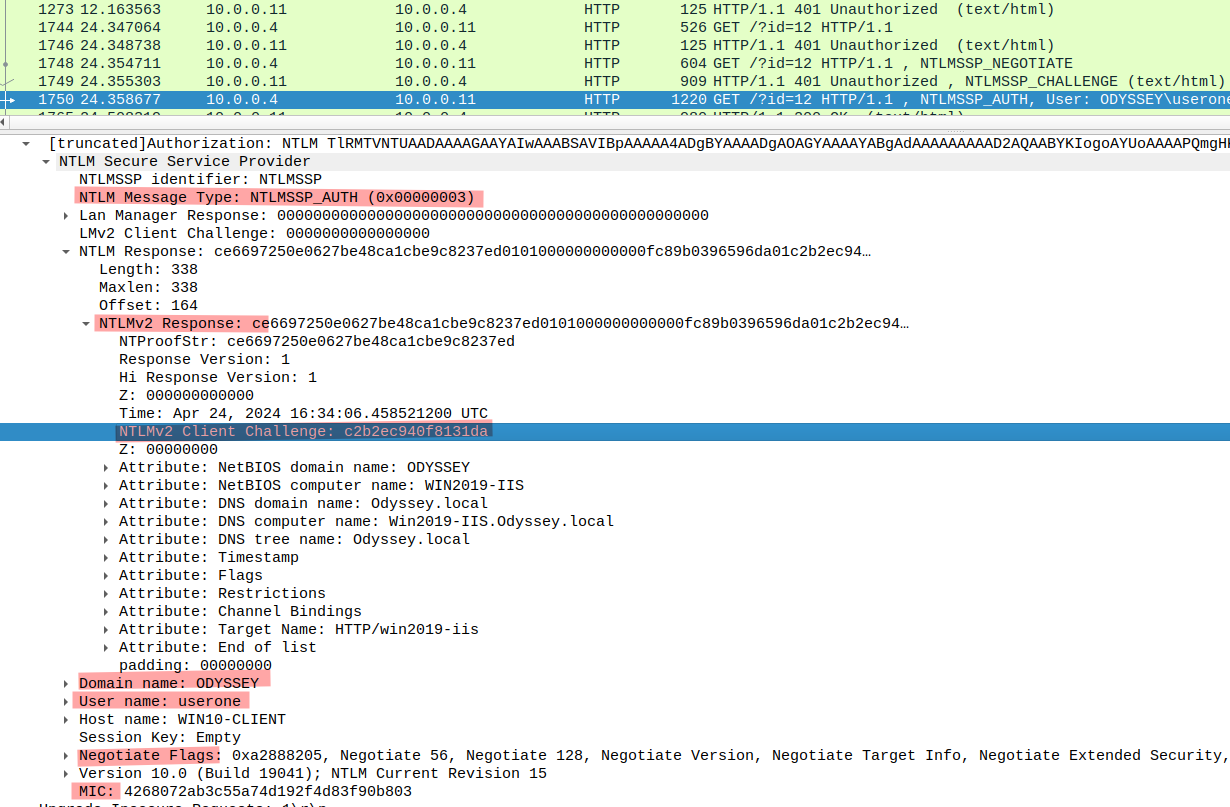

First, we start with an anonymous request. Nothing fancy here. Now, the server (IIS), replies back with an HTTP 401 and with a response header “WWW-Authenticate: NTLM”, letting the client know that the server supports NTLM as an authentication mechanism.

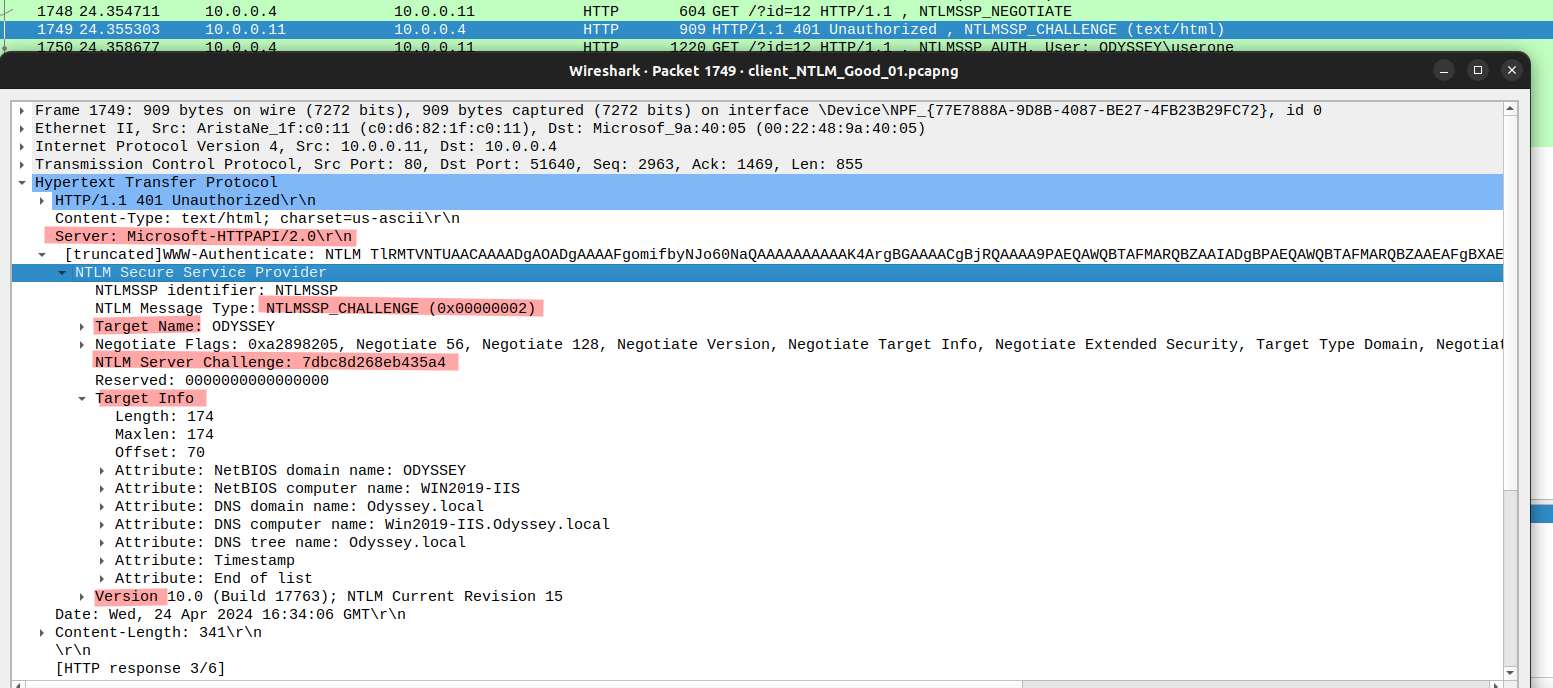

Now, the client replies with an NTLM Type 1 request. This IS the NTLM_NEGOTIATE message that allows the client to specify its supported NTLM options to the server. This contains information regarding the version of NTLM used, and supported security features, among other details.

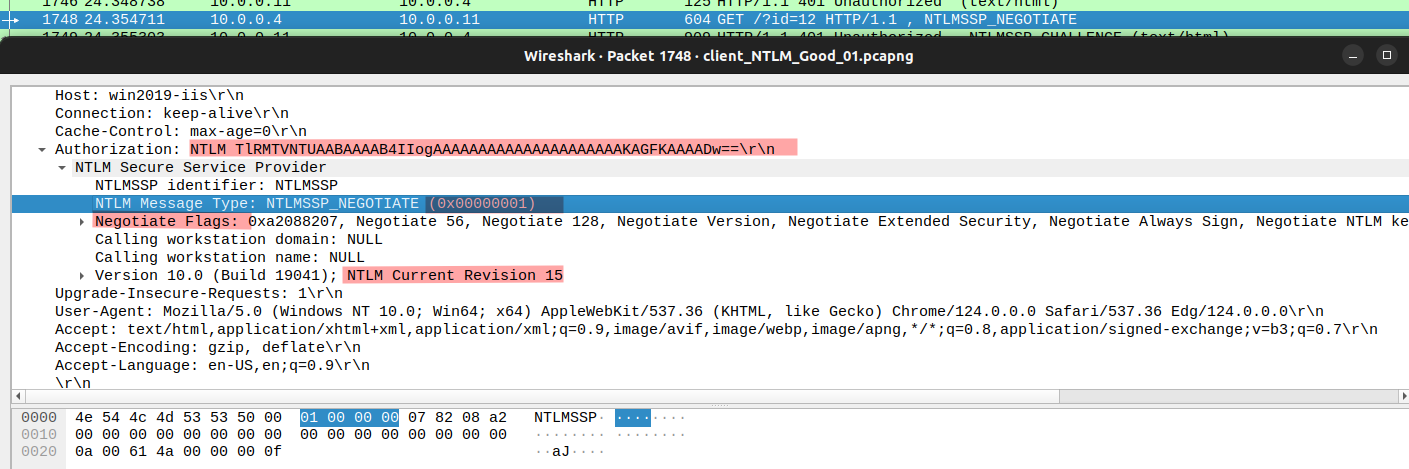

The server now responds with an HTTP 401 and with a Type 2 NTLM message. This IS the NTLM_CHALLENGE message that is used by the server to challenge the client to prove its identity. It is important to note this reply IS NOT from the web server (IIS), but from the machine itself. The response is from the HTTP.SYS driver. This can be identified by the value of the response header called “Server”. In this case, the value is “Microsoft-HTTPAPI/2.0”, hence this is HTTP.SYS responding. In other words, authentication takes place in kernel-mode, not in user-mode, where authentication would take place inside IIS’s worker process(w3wp.exe).

Anyway, this Type 2 NTLM Message contains security features supported by the client, features required by the server, version, and most importantly, the server challenge, the random 8-byte generated string.

- NTLM Server Challenge: 7dbc8d268eb435a4 (hexadecimal).

We are almost done.

Now, the client replies with a Type 3 NTLM message. This IS the NTLM_AUTHENTICATE message and this is the response from the client to the challenge the server sent (NTLM_CHALLENGE). This contains the client’s authentication information derived from the user’s password and the challenge sent by the server in the Type 2 message. It also contains the client challenge, an 8-byte random string generated by the client and used for its calculations.

- NTLM Client Challenge: c2b2ec940f8131da

Specifically, the client response to the challenge is contained in the “NTProofStr” variable. The 16-byte value, aka Value3.

- NTProofStr: ce6697250e0627be48ca1cbe9c8237ed

All this information is passed to the server Base64 encoded. If we take a look at the Authorization header we can see the Base64 value with all this information:

TlRMTVNTUAADAAAAGAAYAIwAAABSAVIBpAAAAA4ADgBYAAAADgAOAGYAAAAYABgAdAAAAAAAAAD2AQAABYKIogoAYUoAAAAPQmgHKrPFWnTRkvTYP5C4A08ARABZAFMAUwBFAFkAdQBzAGUAcgBvAG4AZQBXAEkATgAxADAALQBDAEwASQBFAE4AVAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAADOZpclDgYnvkjKHL6cgjftAQEAAAAAAAD8ibA5ZZbaAcKy7JQPgTHaAAAAAAIADgBPAEQAWQBTAFMARQBZAAEAFgBXAEkATgAyADAAMQA5AC0ASQBJAFMABAAaAE8AZAB5AHMAcwBlAHkALgBsAG8AYwBhAGwAAwAyAFcAaQBuADIAMAAxADkALQBJAEkAUwAuAE8AZAB5AHMAcwBlAHkALgBsAG8AYwBhAGwABQAaAE8AZAB5AHMAcwBlAHkALgBsAG8AYwBhAGwABwAIAPyJsDllltoBBgAEAAIAAAAIADAAMAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAACAAADgVsWuGUuudxJLbNTffAWQ0RJlQ6CES32bKa81nWM7zCgAQAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJACAASABUAFQAUAAvAHcAaQBuADIAMAAxADkALQBpAGkAcwAAAAAAAAAAAA==

If you are curious, you can use an ntlm parser and see the content:

$ ntlm-parser TlRMTVNTUAADAAAAGAAYAIwAAABSAVIBpAAAAA4ADgBYAAAADgAOAGYAAAAYABgAdAAAAAAAAAD2AQAABYKIogoAYUoAAAAPQmgHKrPFWnTRkvTYP5C4A08ARABZAFMAUwBFAFkAdQBzAGUAcgBvAG4AZQBXAEkATgAxADAALQBDAEwASQBFAE4AVAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAADOZpclDgYnvkjKHL6cgjftAQEAAAAAAAD8ibA5ZZbaAcKy7JQPgTHaAAAAAAIADgBPAEQAWQBTAFMARQBZAAEAFgBXAEkATgAyADAAMQA5AC0ASQBJAFMABAAaAE8AZAB5AHMAcwBlAHkALgBsAG8AYwBhAGwAAwAyAFcAaQBuADIAMAAxADkALQBJAEkAUwAuAE8AZAB5AHMAcwBlAHkALgBsAG8AYwBhAGwABQAaAE8AZAB5AHMAcwBlAHkALgBsAG8AYwBhAGwABwAIAPyJsDllltoBBgAEAAIAAAAIADAAMAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAACAAADgVsWuGUuudxJLbNTffAWQ0RJlQ6CES32bKa81nWM7zCgAQAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAJACAASABUAFQAUAAvAHcAaQBuADIAMAAxADkALQBpAGkAcwAAAAAAAAAAAA==

object: {

messageType: 'NEGOTIATE_MESSAGE (type 3)',

version: 3,

lmResponse: { length: 24, allocated: 24, offset: 140 },

ntlmResponse: { length: 338, allocated: 338, offset: 164 },

targetName: { length: 14, allocated: 14, offset: 88 },

userName: { length: 14, allocated: 14, offset: 102 },

workstationName: { length: 24, allocated: 24, offset: 116 },

lmResponseData: { hex: '000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000' },

ntlmResponseData: {

hex: 'ce6697250e0627be48ca1cbe9c8237ed0101000000000000fc89b0396596da01c2b2ec940f8131da0000000002000e004f0044005900530053004500590001001600570049004e0032003000310039002d0049004900530004001a004f006400790073007300650079002e006c006f00630061006c0003003200570069006e0032003000310039002d004900490053002e004f006400790073007300650079002e006c006f00630061006c0005001a004f006400790073007300650079002e006c006f00630061006c0007000800fc89b0396596da01060004000200000008003000300000000000000000000000002000003815b16b8652eb9dc492db3537df016434449950e82112df66ca6bcd6758cef30a001000000000000000000000000000000000000900200048005400540050002f00770069006e0032003000310039002d006900690073000000000000000000'

},

targetNameData: 'ODYSSEY',

userNameData: 'userone',

workstationNameData: 'WIN10-CLIENT',

sessionKey: { length: 0, allocated: 0, offset: 502 },

flags: 'UNICODE NTLMSSP_REQUEST_TARGET NTLM ALWAYS_SIGN EXTENDED_SESSIONSECURITY TARGET_INFO VERSION 128 56',

osVersionStructure: {

majorVersion: 10,

minorVersion: 0,

buildNumber: 19041,

unknown: 15

}

}

This is the response from the client. The client proceeds and sends this to the server. Now, the server sends the challenge-response pair to the DC to verify we have the same result.

The DC calculates the expected value of the response and matches it against the response provided. If the response values match, it MUST send back the SessionBaseKey; otherwise, it MUST return an error to the calling application. The server MUST return an error to the calling application if the DC returns an error.

Here is the pseudocode of the algorithms used to calculate the keys in NTLMv2 authentication:

Define NTOWFv2(Passwd, User, UserDom) as HMAC_MD5(

MD4(UNICODE(Passwd)), UNICODE(ConcatenationOf( Uppercase(User),

UserDom ) ) )

EndDefine

Define LMOWFv2(Passwd, User, UserDom) as NTOWFv2(Passwd, User,

UserDom)

EndDefine

Set ResponseKeyNT to NTOWFv2(Passwd, User, UserDom)

Set ResponseKeyLM to LMOWFv2(Passwd, User, UserDom)

Define ComputeResponse(NegFlg, ResponseKeyNT, ResponseKeyLM,

CHALLENGE_MESSAGE.ServerChallenge, ClientChallenge, Time, ServerName)

As

If (User is set to "" && Passwd is set to "")

-- Special case for anonymous authentication

Set NtChallengeResponseLen to 0

Set NtChallengeResponseMaxLen to 0

Set NtChallengeResponseBufferOffset to 0

Set LmChallengeResponse to Z(1)

Else

Set temp to ConcatenationOf(Responserversion, HiResponserversion,

Z(6), Time, ClientChallenge, Z(4), ServerName, Z(4))

Set NTProofStr to HMAC_MD5(ResponseKeyNT,

ConcatenationOf(CHALLENGE_MESSAGE.ServerChallenge,temp))

Set NtChallengeResponse to ConcatenationOf(NTProofStr, temp)

Set LmChallengeResponse to ConcatenationOf(HMAC_MD5(ResponseKeyLM,

ConcatenationOf(CHALLENGE_MESSAGE.ServerChallenge, ClientChallenge)),

ClientChallenge )

EndIf

Set SessionBaseKey to HMAC_MD5(ResponseKeyNT, NTProofStr)

EndDefine

Where:

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

| NTOWF() | Computes a one-way function of the user’s password to use as the response key. |

| HMAC_MD5(K, M) | Indicates the computation of a 16-byte HMAC-keyed MD5 message digest of the byte string M using the key K. |

| MD4(M) | Indicates the computation of an MD4 message digest of the null- terminated byte string M. |

| LMOWF() | Computes a one-way function of the user’s password to use as the response key. |

| ComputeResponse(…) | A function that computes the NT response, LM responses, and key exchange key from the response keys and challenge. |

Good, you can take a break now.

Lastly, I would like to discuss two more things.

We talked about NTLM being a session-based authentication protocol. However, when authentication takes place in kernel-mode, we can make NTLM behave like a request-based authentication protocol.

We can make NTLM request-based when we adjust our server to send “Connection: close” header, forcing the client to close and open a new connection. We did say that closing the connection would make authentication fail, but this is not true when authentication happens in kernel-mode. This is an optimization that happens when authentication is in kernel-mode.

If this is the case scenario would be something like this:

-

Anonymous request for “/index.html”.

- IIS Server 401, informs the client it supports NTLM but it sends “Connection: close”.

- Connection is closed.

-

The client opens a new connection for resource “/index.html” AND provides the NTLM message type 1.

-

As authentication is happening in kernel-mode, the HTTP.SYS driver receives the request and will allow authentication to continue and won’t send “Connection: close” header. The server sends the NTLM challenge.

- The client sends the NTLM Response to the IIS Server and the IIS allows access to the resource.

From IIS perspective, the authentication has been successful while adhering to “Connection:close”.

For the next resource, the same flow will happen. Hence, behaving like a request-based authentication.

However, if authentication happens in user-mode, this will fail!

How can we know if authentication is happening in kernel or user mode?

In IIS Manager > Site > Authentication > Windows Authentication > Advanced Settings > Enable Kernel-mode authentication.

The default is “true”.

The other thing I want to briefly discuss is the Browser behavior on wheter to prompt or not to prompt for user credentials.

First of all, if the Browser already knows that a resource requires authentication (because it rememebered that it uses NTLM), then the Browser sends a Pre-Authenticated message. So, instead of doing an anonymous request and waiting for the 401 of the server saying it suports NTLM, it skips this step and sends the NTLM Type 1 message.

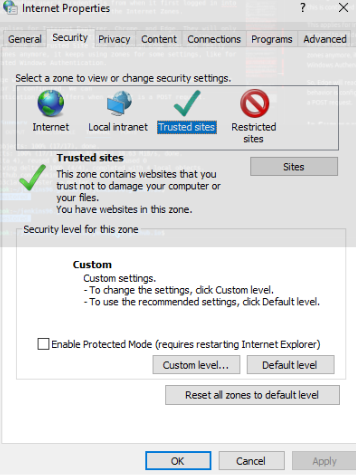

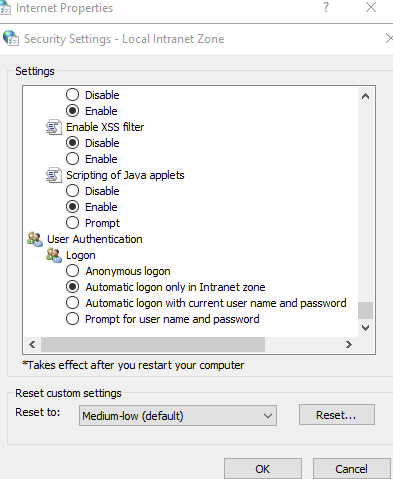

As per the Browser decision regarding asking for credentials or silently sending the user’s credentials from when it first logged in to the machine, this is controlled by the Internet Zones.

This applies to Internet Explorer, Chrome, and Edge. They will only respond to Windows Authentication messages if the URL is either in the Intranet Zone or Trusted Site Zone. Although Edge does not use zones anymore, it keeps using zones for some settings, like for Integrated Windows Authentication.

So, Edge will read values in the Intranet and Trusted Site and see what behavior is configured. We have four possible values here:

- Anonymous logon.

- Automatic logon only in Intranet zone.

- Automatic logon with current user name and password.

- Prompt for user name and password.

If I configure my site in Intranet zone, restart the Browser, now I will not be asked for credentials. But do keep in mind that authentication is still happening.

Now, this is true provided you don’t have any other Chrome/Edge policies that might affect this. For example, if you were to have an Edge policy called “authserverallowlist”, Edge will read values in this policy instead of using values in Intranet and Trusted Sites zones.

In Summary

-

NTLM protocol is slowly phasing out. You should consider other authentication protocols.

-

NTLM is a challenge/response mechanism; where the server challenges the client to provide a specific value.

-

This is a session-based protocol and “Connection: keep-alive” is a must. Although it is true it can be changed so it behaves like a request-based mechanism, but this brings more overhead to the server.

-

Authentication can take place in kernel-mode or user-mode. Kernel-mode offers better performance.

-

The server lets the client know the supported authentication mechanism by appending a response header of “WWW-Authenticate: NTLM”.

-

Authentication information is transferred in Base64. This is relatively safe because this value has passed hashing algorithms. NTLM is comprised of three messages: TLM_NEGOTIATE, NTLM_CHALLENGE, NTLM_AUTHENTICATE.

-

Edge will try to read values in Intranet and Trusted Site zones provided there are no conflicting policies.